Trusty Servant inn sign drawn by Jeanie Mellersh

Hop Press

Issue 7 – September 1982

A rough scan & OCR of the original leaving out adverts & some sections such as the Crossword

View full pdf version 3.2MB download

Go to Previous Hop Press Browse for another Hop Press

Go to Next Hop Press

Contents

- Editorial

- Pub Quiz

- Readers' Letters

- Pub News

- Tasting and Describing Beer - Steve Harvey

- The Trusty Servant at Minstead - Nick Mellersh

- The Anchor Steam Brewery - Ged Wallis

- The Strong Country

- Books on Beer

- Good Ploughman's

- CAMRA Southern Hants Branch

EDITORIAL Hop Press index

Some of our readers may wonder who publishes Hop Press and why. Hop Press is published by the Southern Hampshire branch of CAMRA (the Campaign for Real Ale). Its purpose is to stimulate interest in beer and pubs. Hop Press makes no profit. The magazine is distributed free to landlords for their customers. Our only income is from the few advertisements we carry, and these don't even cover our printing costs. In short, Hop Press is free from commercial interests.

Hop Press would like to involve its readers - that's you, the men and women in our Hampshire pubs. We believe that many of our readers have something interesting to say about beer, brewers, pubs and associated matters. So why not put your thoughts on paper - either as an article or as a letter to the editor. Or, if you've got an idea for an article but you'd like to talk it over, write or phone the editor of Hop Press, who'll be pleased to discuss your idea.

If you read something in Hop Press that you disagree with, write and tell us. We'll publish any reasonable letter, even if we don't agree with what it says. Free speech and the right to enjoy a difference of opinion have helped to make our English pubs the envy of the world. Let's keep that tradition alive.

Pub Quiz Hop Press index

| 1. | Which Winchester pub is said to be haunted? |

| 2. | Which Romsey pub has been, at different times, a guildhall, a workhouse, a house of mercy, and a brothel? |

| 3. | Which country pub has a collection of chamber pots in the bar? |

| 4. | Which Winchester pub has a large collection of miniature bottles? |

| 5. | Which Winchester pub has had four different names in the last five years? |

| 6. | Which Southampton pub brews on the premises? |

Answers on page 12

Readers' Letters Hop Press index

Beer mats

We began collecting beer mats when our daughter, who was the original collector, decided to get rid of them. As many of them had been obtained through our efforts, we could not see them thrown away or given away to someone who had done nothing to collect them. Since then, we have added to our collection, and now have over a thousand different mats.

We have beer mats from all over Australia, from the Pacific islands, and even from England. Our mats feature motels, hotels, clubs, beers, wines, cigarettes, trucks, planes, trains, Scottish castles, whiskies, and Aborigine artefacts. We display them at hobbies exhibitions, stamp clubs, and other such gatherings.

We would be pleased to hear from anyone with an interest in the subject.

Mr and Mrs R Craig

90 Christie Road

Tarro 2322

New South Wales

Australia

Titchfield

Hop Press readers may like to know that the newly-published Titchfield: A History contains a section on the brewery and the inns, with illustrations of one of the old vans, the brewery, and some of the bottle labels. The book costs £3 in paperback, and can be obtained from the Titchfield History Society,

7 Church Street, Titchfield, or from some local bookshops.

George Watts

Open University Winchester Office

Medecroft

Sparkford Road

Winchester

S022 4NJ

PUB NEWS Hop Press index

The Royal Oak in Winchester has a new landlord, John Moore. And the news is good for real ale drinkers and jazz enthusiasts. John will continue to serve real ale, and he is keeping on the Monday and Thursday jazz fixtures. The pub will be closed for most of November for extensive redecoration and some alteration. John assures us that far from ruining the character of the pub, the alterations should enhance it. Some of the ancient woodwork will be uncovered, gas lamps will be installed, and a proper stage will be built for the jazz bands. The theme of the pub will be real ale and trad jazz. And most enticing news of all - there will be three additional real ales on sale, but John wasn't free to disclose what they'll be.

Still in Winchester, the Mash Tun in Eastgate Street is now open, and selling a variety of real ales. The Mash Tun, which is associated with the Ringwood Brewery, will eventually be brewing on the premises.

The Black Boy in Wharf Hill. is currently serving Tiger bitter from Burton-on-Trent brewer Everards.

Renovation is under way at the Leigh Hotel in Eastleigh. Watch this column for any further news.

The Bush at Ovington is now selling Whitbread's beers.

That's all the pub news we've got for you this time. Landlords of houses serving real ale are invited to submit items for Pub News direct to the Editor, Hop Press.

Tasting and Describing Beer Hop Press index

Is beer simply beer - all more or less the same - or is it, like wine, possessed of many subtleties of flavour? You can perhaps remember, as I can, the days when you simply went into a pub and asked for a pint of bitter. None of today's agonising over what particular brand is available and whether it's real ale or not. Oh for such simplicity today! But the irony is that in a way it was the Big Bad Brewers themselves who took the simplicity out of beer drinking. It was back in the late sixties that we found it increasingly difficult to simply go into a pub, order a pint of bitter, and get what we wanted. Because it was about that time that the drink many of us had grown up on began to disappear. In its place was a much fizzier, blander drink called keg bitter. At first, some of us quite liked it. After all, it was always clear, always bright, which was more than you could say of some of the traditional ales - and provided you could cope with the gassiness, a few pints still made the world seem a better place. Trouble was, we soon began to miss the taste of true British beer, with its distinctive hoppy tang - something quite absent from the new-fangled wonder-beers. The rest is history: how CAMRA came into being; how the Big Brewers laughed at us; how we struck a chord with the beer-drinking public; how the Big Brewers wiped the smiles off their faces; how the small local brewers who had kept faith with true draught beer saw their fortunes improve; how real ale changed from a fad to a commercial success again. But you can never quite turn back the clock. One result of our increased awareness of the subtleties of draught beer is that we've learned to distinguish more clearly between the different beers.

Distinguishing is one thing - describing the difference is quite another. The Good Beer Guide published annually by CAMRA includes a brief description of almost every true draught beer available in Britain today. But, if we're honest, we'd have to admit that we've still got a long way to go in learning how to capture in words the marvellous subtleties of flavour in our heritage of different draught beers.

What are the differences that we can try to describe? Let's start by looking at the basic ingredients of beer: malted barley, hops, yeast, and water. They all play their part in determining the flavour of the pint in your glass, but some are easier to identify then others.

The importance of the water used in brewing is well known. Not for nothing is Burton-upon-Trent famous as a brewing town. Its hard water, rich in magnesium sulphate, is ideal for producing classic pale ales and draught bitters. (Magnesium sulphate is otherwise known as Epsom Salts, which may explain the effect that these excellent beers have on some drinkers!) Nowadays, though, the quality of the local water is less important than it once was. With the advances in chemical science, most brewers can adjust the chemical make-up of their water to suit the type of beer they wish to brew.

Yeast has a critical effect on the finished beer. The head brewer at Marston's in Burton-upon-Trent has said that if his yeast strain began to change, he'd notice the difference within three brews, and the average drinker would notice it within five brews. Most brewers would agree that the choice of yeast is of the utmost importance. The point is well illustrated by the fact that Gale's, the Hampshire brewers, use different yeasts for different beers. And when, a year or two ago, the Ringwood Brewery needed a yeast. they went to all the trouble of having one brought down from the Belhaven Brewery in Scotland. That's the way brewers feel about yeasts. Nevertheless, yeast is tricky territory for most of us consumers.

Where we can begin to pronounce with a little more confidence is in the area of hops and malt. Is a beer predominantly malty, or predominantly hoppy? Or it may be balanced right in the middle of the hop-malt spectrum - in which case, surprise surprise, it's described as well balanced. Let's look at some locally available examples, Most of Eldridge Pope's 'Huntsman' beers are malty - especially their Dorset Original IPA and the strong Royal Oak. On the other hand, Courage's Best Bitter is a fine example of a well-hopped beer.

Another factor that's not too difficult to identify is the sweetness of a beer. If the brewer stops the fermentation process before all the malt (and in some cases, sugar) has been fermented out, there will be some residual sweetness in the beer. What's more, the unfermented malt will add body to the beer, so that it feels heavier, more full-bodied. Generally speaking, brewers leave more sweetness and body in their stronger beers. There's a good reason for this: if a beer is high in alcohol, giving it more body helps the drinker to adjust the speed at which he drinks it. In other words, the fullness of body acts as an indication of the beer's strength. Again, let's look at a local example. Try comparing Gale's very strong HSB with their ordinary bitter. Not only is HSB noticeably sweeter, it's got much more body. You simply can't drink it fast - which is probably just as well!

So far we've looked at the fundamental ingredients of traditional beer. There are other ingredients that some brewers use to give distinctive qualities to their beers - such things as flaked maize, various types of sugar, caramel, molasses, liquorice, and so on. While you may not be able to pin down the ingredients the brewer has used, you will notice certain flavours that seem to be present in one beer and not another. For example, I find that some bitters have what I call a 'smoky' flavour: Badger Best Bitter and Kent brewer Shepherd Neame's bitter are examples. To my palate, Whitbread's Strong Country Bitter has an 'appley' taste.

Finally, don't forget colour, which affects our perception of a beer. Some bitters, such as Marston's, are fairly pale. Others are rather dark. Generally, brewers who produce a highly hopped bitter tend to favour a paler colour, while those who produce a maltier brew tend to favour a darker colour. Of course, there are various types of malted barley available to the brewer, and these will in themselves affect the colour. Guinness gets its very dark colour because the brewer uses an unusually high proportion of dark roasted barley.

These, then, are some of the differences you can detect between one beer and another. Putting the difference into words isn't easy - describing what the taste buds perceive has always been difficult. Nevertheless, I feel that people writing about beer today are rather inhibited about describing it. After the usual 'a well-hopped brew', 'a strong, malty beer', and 'a well balanced bitter', they seem to run out of ideas. To encourage you to give more thought to the many excellent local brews you can sample, Hop Press is running a competition among readers for the best original descriptions of any four locally available draught beers. Here are the simple rules:

<table> <tr> <td>1.</td> <td>Describe any four locally available real draught beers in your own words. We'll be looking for originality, so try to avoid following the pattern of existing descriptions in books on beer.</td> </tr> <tr> <td>2.</td> <td>The four draught beers you describe need not all come from one brewer; in fact, we'd prefer it if they don't. The beers must be available in southern Hampshire.</td> </tr> <tr> <td>3.</td> <td>Send your descriptions to The Editor, Hop Press, 18 Peverells Road, Chandlers Ford, Hants, SO5 2AT. We will award a copy of the current edition of Real Ale in Hampshire to the reader who submits what we judge to be the most apt and original descriptions. The Editor's decision will be final.</td> </tr> <tr> <td>4.</td> <td>We reserve the right to publish entries.</td> </tr> <tr> <td>5.</td> <td>Closing date: 30 October 1982.</td> </tr> </table>

The Trusty Servant at Minstead Hop Press index

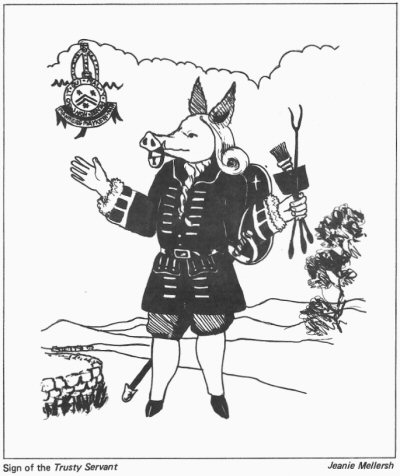

Sign of the Trusty Servant - Jeanie Mellersh

A Trusty Servant's portrait would you see?

This emblematic figure well survey.

A porker's snout not nice in diet shows,

A padlock shut no secret he'll disclose.

Patient the ass his master's wrath will bear,

Swiftness in errand the stag's feet declare.

Loaded his left hand apt to labour saith,

The vest his neatness, open hand his faith.

Girt with his sword, his shield upon his arm,

Himself and master he'll protect from harm.

This is the strange rhyme you will see under the even stranger beast on the sign of the Trusty Servant at Minstead in the New Forest,

"What does it mean, where does it come from, and how did it get to Minstead?" These are the questions that most people ask.

Nobody knows when it got to Minstead. There's been a pub on the site of the Trusty for hundreds of years. And it may have been called the Trusty for that length of time. Certainly it has been called the Trusty for as long as anyone who lives in Minstead can remember.

We know where it came from, or can anyway make a very good guess. It was probably painted by a travelling sign painter who stopped at Minstead after a visit to Winchester, because the sign and the rhyme are copied from a picture that belongs to Winchester College, The motto of Winchester College, "Manners Makyth Man," is at the top of the sign, just as it is in the painting.

The most endearing story about what it means is that the curious figure with a pig's snout, a padlocked mouth, and ass's ears was a satirical portrait of one of the king's ministers, done by a Winchester painter. Sadly it seems as if this cannot be true. The same picture and a similar rhyme occur in many other places in Europe, especially in Germany, Many of the others predate the Winchester painting. The Trusty Servant picture and rhyme were apparently a medieval attempt to symbolise all the best virtues of one servant in a single amalgamated beast.

The virtues of a trusty servant are described in the rhyme. Starting from the top, the perfect servant has a pig's snout to show that he is not a fussy eater, ready to eat anything including the leftovers that were not good enough for his master. He has ass's ears, not because he listens to secrets (his mouth is padlocked, remember) but to show his patience when he is beaten by his master. But he is unlike an ass when it comes to doing things - his stag's feet show how fast he will run to get things done. The rest of it you can read in the rhyme for yourself. (I have often wondered, incidentally, what sort of labours the tools in his left hand are for, They always look to me like a set of fire irons.)

And the pub itself? Well it's still a village pub with a lunchtime and evening set of regulars. (It has real ale of course, or you would hardly be reading about it here.) Come along one night and see. You might find sweet chestnuts being boiled on the stove - the crop looks good this year - or if you come on a Friday night you will find a sing-song in progress.

If you want to see the sign, you might do better to come at lunchtime. Among the lunchtime regulars you will find Bill Knight. He can tell you what it was like to be a trusty servant, for he was gardener and handyman to the Duchess of Westminster when she owned one of the big houses in Minstead, He looks back on those days with pleasure, but still has rather a different viewpoint about a trusty servant from the writer of the Trusty Servant rhyme.

The Anchor Steam Brewery Hop Press index

During a recent trip to San Francisco, I arranged a visit to the famous Anchor Steam Brewing Company. A phone call was all that was needed, and the following day I joined a dozen other people for the afternoon tour.

The Anchor Brewery is an imposing cream building surrounded by rather tawdry light industries. By good luck I arrived just in time to photograph a departing dray in its smart Anchor livery,

The tour of the brewery lasted about an hour and was conducted by an amiable young employee who introduced himself simply as Jim. He told us how the brewery was saved from closure in the 1960s by the present owner, a businessman who was reluctant to see a piece of San Francisco's heritage disappear. Today, the brewery employs fifteen people. They brew on three days a week, and maintain the equipment on the other days.

The beer is unusual for the U.S. in that only the best traditional ingredients are used: malted barley, hops, yeast and burtonised water. And for the most part only traditional brewing methods are used. The term steam has nothing to do with the brewing process, but dates from the mid-19th century when all West Coast beer was brewed at higher temperatures than usual because of the climate. The resultant brew was naturally highly carbonated, and very frothy when served. As a result the locals got into the habit of asking for a glass of 'steam' - a name which has stuck ever since.

Nowadays they use the conventional continental lager process. In fact the main equipment was purchased from a German brewery. One thing that struck me throughout the tour was the spotlessness of the equipment and the building. This was exemplified when we were shown the open fermentation vats. Four of these are installed in a sterile room where, after the yeast has been pitched, the wort ferments for 72 hours. During that period nobody is permitted to enter the room. Prior to entering the vats the wort is cooled by heat exchangers; the cool water heated by this process is used for the next brew, thus saving energy.

The only step which prevents this delicious beer from being real (in the CAMRA sense) is that the cooled wort is filtered and pasteurised, making it a dead beer. When I asked Jim why they do this, he explained that it increases the shelf life to over six months. He was at pains to point out, however, that no chemical or other additives are used whatsoever. They are starting to ship further afield, and they need to keep their reputation of producing America's finest beer. Nevertheless, it would be interesting to see how a cask or bottle conditioned version of Anchor Steam would be greeted by local people (including San Francisco's own CAMRA members).

At the end of the tour, we were taken to the hospitality room to sample the products. They brew two beers regularly: a tawny lager and a black porter. At Christmas they also brew a stronger Christmas Ale. The lager ( original gravity 1046) is nutty and only lightly carbonated, rather reminiscent of some Belgian real lagers. The porter (OG 1051) is smooth, and tastes something like bottled Guinness. We were fortunate in that there was still some Christmas Ale remaining. It's a well-hopped, stronger version of the lager - very tasty.

During the hospitality session, I was able to talk to other visitors and some of the staff about CAMRA and its aims. The staff were aware of CAMRA but the visitors had not been and were fascinated that such an organisation should exist. Prompted by their enthusiasm, I took the opportunity to hand round membership forms. We may yet have a branch in San Francisco!

If you are lucky enough to go to San Francisco, the Anchor Brewery is well worth a visit. I have also learned since that nearby is the New Albion brewery, which produces a real bottle-conditioned ale. Ah well..... perhaps next time.

Page 12 - ANSWERS TO PUB QUIZ

1. The Heart-in-Hand, Bar End Road.

2. The Tudor Rose, Cornmarket.

3. The Leckford Hutt, Leckford.

4. The Bell Inn, St Cross.

5. The Mash Tun,. Eastgate St. Previously the Halcyon, the Fighting Cocks, and the Lawn Tavern.

6. The Frog and Frigate, Canute Road.

The Strong Country Hop Press index

The town of Romsey, nestling in the lower Test Valley near the edge of the New Forest, is now famous for its Royal Honeymoons - but it was once well known as a brewing town.

When Romsey Abbey was active, there were many travellers requiring accommodation and refreshment. Consequently, there were many inns and pubs. In the eighteenth century, most innkeepers and publicans would brew the beer that they sold, but gradually some found it more economical to buy their beer from other brewers. From time to time, some of these wholesale brewers found themselves owning pubs through possession resulting from unpaid debts. So, almost by accident, they started expanding, and owning houses 'tied' to their beer. After the collapse of the town's wool industry in 1760, brewing became Romsey's principal business. By 1800, only one third of the town's pubs still brewed their own beer, and certain companies were beginning to gain in strength.

Notably, Trodd and Hall's brewery in the Horsefair (subsequently to become Strong's) owned four pubs, of which the Star is the only one still trading. The Bell Street brewery also owned four pubs, and Galpin's brewery in the Hundred owned several. These three were the main brewers of the day. They quickly realised the advantage of the beer tie and the control it gave them. This lead to the tying of properties as a matter of policy.

With the vast improvements being made in transport, expansion into the traditional territories of other breweries led to fiercer competition, in which the least successful brewers were bought out or went bust.

In 1883 Trodd and Hall's Horsefair brewery was bought by one Thomas Strong, whose surname was later to become synonymous with Romsey and the surrounding area. By now, they owned ten public houses. Then in 1886, after the death of Thomas Strong, David Faber arrived on the Romsey brewing scene. Within one year he bought the Bell Street brewery, the Hundred brewery and Strong's brewery. He also acquired many malthouses and pubs in the town, thereby gaining almost total control of brewing in the heart of the area that became known as the Strong Country.

The home brewers began to close down under the pressure of competition from the bigger brewers. In 1900, Cave at the Red Lion in the Hundred and Holloway at the Woolpack in Middle bridge Street finally ceased brewing their own beer. The only remaining home-brewer was then 'Balacker' Smith, whose family had been brewing in the thatched cottage in Love Lane since the eighteenth century.

'Balacker' Smith was something of a legend, having fought a famous battle with his neighbours, the gasworks, whom he blamed for polluting his well. They in turn blamed his drains, until he quite illegally connected them to the gasworks' sewer. Smith used to expect any debtors from his other properties to drink in his pub, the Spotted Cow in Love Lane, every night. However, in 1926, Smith retired. He had been undermined finally by the use of glass drinking vessels, which led his customers to expect clear beer - a luxury Smith seemed unable to supply. At last, Strong's brewery was without any rival in Romsey.

Strong's now owned twenty of the town's many pubs. (There was one pub for every 141 inhabitants - twice the national average.)

In 1969, Whitbread gained control of Strong's as part of their national expansion campaign. And in 1981, they discontinued brewing in Romsey. Strong Country Bitter is still sold in twelve of Romsey's sixteen pubs, but the beer is now brewed in Portsmouth. Probably for the first time in its history Romsey is without a brewery.

Books on Beer Hop Press index

The Beer Drinker's Companion by Frank Baillie. David and Charles, 1975. (Out of print)

Describes the various types of beer, serving beer, and the brewing process. Chapters on the hop plant and the brewer's dray. Contains a directory of the regional brewers of Great Britain. A little out of date now, but still a sound treatment of the subject by one of our best writers on beer.

Beer and Skittles by Richard Boston. Collins, 1976. (Out of print)

Starts with a historical look at brewing, then deals with types of beer, the brewing process, and serving beer. Next, an excellent chapter on what happened in the industry in recent times. Goes on to deal with beer in the home, then has a long and entertaining discussion of pubs and pub life. Ends with a brief survey of regional beers. Very readable.

The Penguin Guide to Real Draught Beer by Michael Dunn. Penguin Books, 1979. 208 pages, paperback £0.95

Chapters cover be in the brewery and at the pub, a history of brewing in Britain, the growth of the Big Six brewers, local brewers and the real beer revival, and a detailed guide to the real beer breweries of Britain. A sound, factual treatment, good value for money.

Beer and Brewing by Dave Laing and John Hendra. Macdonald Guidelines, 1977. 96 pages, paperback. £1.45

An attractive pictorial booklet. After a section on beer in general, the main subject is home brewing, which is clearly described and excellently illustrated.

Good Beer Guide 1982. CAMRA, 272 pages, paperback. £3.95

Published annually by CAMRA. The current edition lists some 6,000 selected pubs in Britain serving real ale. Also contains a complete list of real ale breweries and their beers, with the original gravity of each beer and a brief description. Useful for the travelling real ale enthusiast.

Real Ale in Hampshire 1981-82. CAMRA. £1.00

Lists all pubs in Hampshire known to be serving real ale at the time of going to press. Invaluable for the beer drinker who wants to know what beer is available where. Also lists other details of each pub's facilities, Available from some pubs, or direct from G. Wallis, 1 Monk's Road, Winchester (Win 54666 ). Special offer price to Hop Press readers: 50p

So Drunk He Must Have Been to Romsey - A History of Romsey's Pubs and Inns. Lower Test Valley Archaeological Study Group, 1974. 68 pages, paperback, £0.75

An interesting account of Romsey's pubs, including many that are no longer in business.

The World Guide to Beer edited by Michael Jackson. Mitchell Beazley, 1977. 246 pages, hardback. £12.95 (Also available in paperback).

A large-format, lavishly illustrated book describing beers from all over the world. Beautiful photographs, illustrations and maps, plus authoritative text. A book most beer enthusiasts would like to own.

Good Ploughman's Hop Press index

You've probably noticed that Ploughman's Lunch can mean anything from a chunk of stale bread, some hermetically sealed cheese and foil-wrapped butter, on the one hand, to a lavish concoction of bread, cheese, butter, pickle, onion, lettuce, tomato and cress on the other. But what makes a good Ploughman's? Well the whole point of a Ploughman's lunch is surely that it is simple, nourishing, and delicious. After all, you can't do a lot of ploughing on lettuce and cress. Manual labour demands calories - so the essential ingredients of a Ploughman's Lunch are bread and cheese. Good, fresh bread, and well-flavoured, crumbly cheese. The kiss of death for the Ploughman's Lunch is fridge-cold plastic cheese in a plastic wrap and too little butter in fiddly foil packs. Salad trimmings are nice, of course, but they aren't a substitute for bread and cheese in proper quantity.

What you get - and what you pay - for a Ploughman's Lunch varies so much from one pub to another that Hop Press invites readers to submit nominations for our Good Ploughman's rating. Send us your nominations, which should include the name of the pub, a description of the Ploughman's they serve, and why you consider it to be superior.

As far as possible, we'll follow up your recommendations. Then we'll publish the names of the pubs that we agree merit our Good Ploughman's rating.

Nominations, please, to the Editor.

CAMRA Southern Hants Branch Hop Press index

This issue of Hop Press went to the printer too early to include the October diary. There's one more September fixture:

| Wednesday 29 September: | Darts Match 8.00 pm, Railway Inn, Winchester |

For details of October's events, contact either Mike Jones (West Wellow 22079) or Nigel Parsons (Southampton 31517).

If you are not a member of CAMRA but would like to join, please complete the membership application below. As a member, you'll receive a copy of the national magazine What's Brewing every month, which keeps you in touch with the world of beer and brewing. You will also be able to join in local branch activities. And most important of all, you'll be doing your bit to help ensure that real draught beer and traditional pubs don't get 'phased out' in the name of progress.

APPLICATION FOR MEMBERSHIP

I/We wish to become a member/members of the Campaign for Real Ale.

[ ] I enclose £ 7 for full membership for a year

[ ] We enclose £ 7 for joint husband and wife membership for a year

Name (block capitals) ............................................

Address (block capitals) ........................................

...............................................................................

Signature(s) .................................. Date ..................

Please make cheque payable to Campaign for Real Ale Ltd and send completed form to Membership, CAMRA, 34 Alma Road, St Albans, Herts, ALl 3BW.

Hop Press issue number 7 – September 1982

Editor: Steve Harvey

18 Peverells Road

Chandler's Ford

Hants

SO5 2AT

Tel: Chandler's Ford 67207

hop-press@shantscamra.org.uk

©CAMRA Ltd. 1982

|

© 2026 CAMRA Ltd. All rights reserved. Campaign for Real Ale, Southern Hampshire Branch Pages supplied by & updated by the Webmaster: Pete Horn [View Site Disclaimer, Personal Data Handing, and Cookie information] [Site History] |